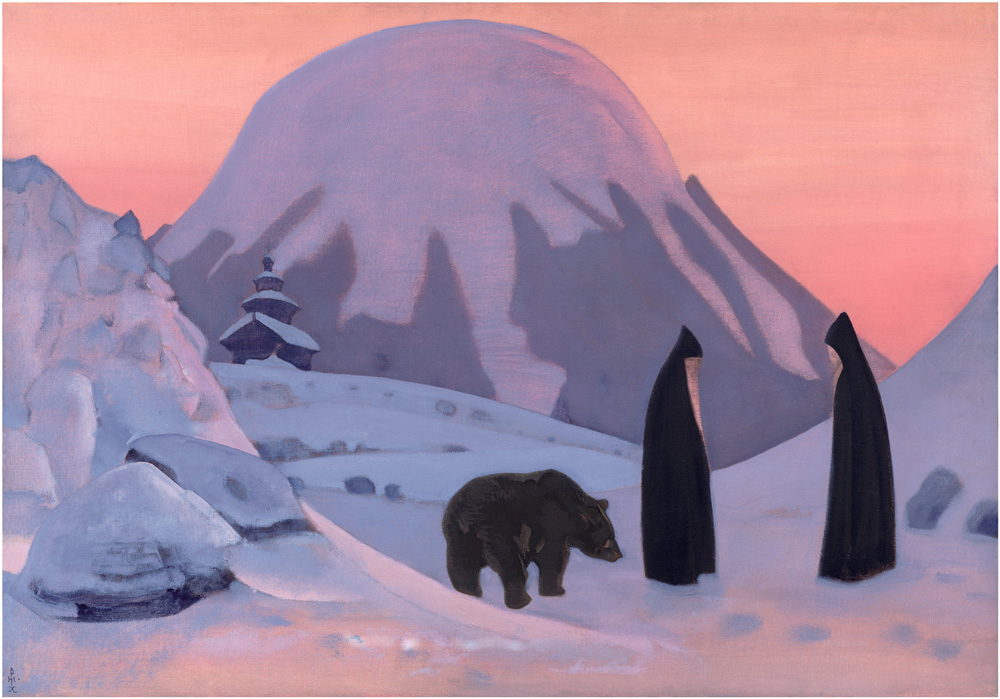

(Painting from the Roerich collection and featured in the film, “Death as Life.”)

While I am working on my latest film, the airport has become far too familiar. On my way out of town for film shoots, I often stop by the bank to make a deposit in my safety deposit box. A habit of filmmakers is to make duplicate copies of their captured footage on hard drives, in fire safes, and in off-site storage. The safety deposit box belonged to my mother. Since my mother’s death, every time I am there, I revisit the memory of the day she took me to put my name on the account. It is a fond memory that makes me smile inside. She was excited to show me what she had stored for safekeeping. Nothing in it was of much monetary value, but the treasured trinkets of jewelry belonged to her mother, who died when my mother was very young. The day Mother invited me to see the items that she valued by the weight they had on her heart, I invited her to do the unimaginable. It didn’t take but a nudge for her to partake in such a decadent pleasure. She finally allowed herself to take them home to enjoy.

Waiting for a bank employee to let me inside the room, I was conscious of every passing moment, since I had a flight to catch. When the bank manager met me, we walked toward the vault where all the safety deposit boxes were stored out of reach of anyone without a key. The manager immediately noticed that my box was tagged, indicating my mother’s death. How did they know, I wondered. I guess with technology, the deceased’s Social Security number is flagged in a pool of data for other institutions to access as easily as information about a stolen credit card.

Occupied by the memories of my mother and feeling hurried by the lack of time I had left to spare, I was oblivious to most of what the bank clerk said, until I heard, “You need to bring in a copy of your mother’s death certificate, so that we can take her name off of the safety deposit box.” I was shocked by my reaction. I tearfully pleaded to the bank manager that I could not take my dead mother’s name off as a joint owner. Where did that reaction come from? Simultaneously I was struck with sadness and stunned by its inappropriateness. Still, I could not stop myself from trying to convince the bank manager that the protocol was wrong and unnecessary. As I supported my case, my behavior and the lack of reasoning behind my argument were hard to justify. I guarantee that her management training failed to prepare her for the seemingly crazed woman begging her not to remove her dead mother’s name off a piece of paper.

Grief is that way. It appears out of nowhere to remind you that it hasn’t gone far. The sightings aren’t given a calendar to reference, nor do they care about being inconvenient. In that moment, the pain and sadness is as fresh as if the death happened yesterday. As one woman in my film, Death as Life, said, “Grief is a beast; it can sneak up on you at any time.”

Foreign to our Western culture, some cultures combine death with life. In 2002, I visited the enchanted land of Tibet. While Tibetans lacked the technology and daily conveniences we take for granted, it was easy to respect them for their culture, rich with a knowing about life that permeated everything they did.

For those of us who trekked across the world to experience the traditions of this far-off land, it would have been a miscalculation of the itinerary if the cremation grounds weren’t part of the visit. The cremation grounds are a significant visible contrast to the way we isolate death in the West. I witnessed many people who lost their loved ones at the cremation pyre. Oddly, they were singing and chanting. I can’t say they seemed happy, but they didn’t seem immersed in sorrow, either. I represented the US very well on that visit. As the smell filled my nose and the smoke filled my lungs, tears ran down my cheeks, while I cried for those who lost loved ones. At least I thought that was what my tears were about. It was much later when I recognized that the sneak preview of death that day raised my fears of losing someone close to me. When we avoid death, and then it happens, we are left without resources to contain the intense feelings that follow.

In our Western culture, death is a secret rite of passage we all know we will take, but we somehow believe we can avoid it. The energy to hide from death is funneled into things such as entering into and staying in unhealthy relationships, overworking, and other emotionally and substance-addictive distractions that keep us too occupied, so death seems far away.

Death wants to be noticed, however. When we deny its existence, we deny life. Life is constantly moving, and to think we can stop the movement by clinging to what we want is like jumping in front of a semi truck on the freeway, believing we can stop it. With the movement of life, there is always death, from physical death to the death we experience as change.

When I set out to create the film, Death as Life, I wanted to break the barrier that surrounds the ultimate death — physical death. As fate would have it, I was my test audience. During the making of the film, I lost the three people closest to me. My two best friends died, and my mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. I knew then that I was onto something, because working on the film helped me heal. One of my co-editors was then going through a major breakup, and she said that the film helped her tremendously. My conclusion is that when we accept death as part of life, it becomes easier to accept change. Don’t get me wrong; loss brings with it intense emotions, but if we befriend the sorrow, we have an ally. The sorrow of death opens our heart to acceptance. With acceptance, we allow life in; not the life we think we can control and mold, but the life that gives us inner meaning.

When the assisted-living facility called me in the middle of the night to let me know my mother had died, I kept repeating, like a mantra, “What am I going to do?” The attendant on the other end of the phone tried to talk me through what I needed to do physically, but I was not referring to the physical actions I had to take. I couldn’t imagine my life without the woman who had loved me since birth. I suddenly felt very alone in the world.

My mother was a fiercely independent woman who was stripped of all her dignity and freedom when she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. She fought her diagnosis for more than five years, but in the last six months of her life, she finally surrendered and accepted the end of her life as she knew it. During that time, she was so full of love that it was sometimes hard to take it all in. I believed she crossed through the veil that separates planes of existence. I had the opportunity to sit in front of a woman who radiated love, and often I chose to focus on the dysfunction of the assisted-living facility she was in. What an appropriate sampling of life. We push away love, because if we really feel it at the wellspring of our existence, fear whispers “death” with an inaudible but piercing pitch.

The holidays are symbolic of celebration. They come with a lot pressure to be joyous during a time we can’t help remembering people who are no longer with us on our physical journey. However, their love is with us. I don’t mean to sound like I have a Pollyanna voice, but when we fear death, it may be difficult to hear what I am saying, because fear overshadows love.

During the holidays I strive to be grateful for all the love that has touched my life. Denial, anger, bargaining, and depression are the breaks I may need to take here and there, before I fall into acceptance. When I accept loss as part of life, I have a glimpse of being free from fear; not the fearlessness used to prove I could do something, but the fearlessness that reaches inward. It is an inner knowing, a knowing that is governed by intelligence incomprehensible to my human brain. Mystics call it the peace that surpasses understanding. It is where death and life are one, and not opponents that coerce us to choose sides.

Written by Sofia A. Wellman